One of many

trip reports under the

SilGro home page for Alan Silverstein and Cathie

Grow.

Email me at

ajs@frii.com.

Last update: February 18, 2025

(Previous trip report: 1987_0704-05_CastlePeak.htm)

(A

Fourteener

trip report.)

Nearby: Photos (click to enlarge) of the Challenger Point summit after

placing the plaque, and a close-up of the plaque by

Dwight Hunter

during the first (preparation) small-group trip to Columbia Point. This

was taken 16 years to the day after the plaque was installed. Note the

apparent lightning damage to the "w" in "Crew".

Related webpages:

Contents:

One weekend we placed a bronze memorial plaque on top of Challenger Point, Colorado, 14080+'. What began in my mind as a wild idea last January culminated with five people and seven hours on a remote mountaintop on a Sunday. We came together from Fort Collins, Boulder, and Colorado Springs, never having met before. We shared a common interest in mountaineering and the space program.

This is a longer report than usual because there is a lot to tell, including a bit of background. We did something challenging and unusual, even for people who spend their summers climbing high mountains. I write these reports for my own memoirs, post them to hpnc.general [a "news group" inside HP in the old days, now on my website in HTML format] because others have shown interest in reading them, and in this case, I also shared the report with various entities outside Hewlett-Packard, so I spelled out some things (like "HP").

Challenger Point was named for the Space Shuttle which exploded soon after liftoff on January 28, 1986, killing its crew of seven. Dennis Williams, a Colorado Springs engineer, proposed the name to the US Geological Survey (USGS) Board on Geographic Names (BGN) in 1986. He climbed the then-unnamed mountain himself on September 21. The BGN approved the name on April 9, 1987.

Challenger was the high point of a long, narrow ridge on the northwest shoulder of Kit Carson Mountain, 14165', 37.98021 -105.60669, in the steep Sangre de Cristo Range. Challenger and the main peak of Kit Carson were about 2000' apart. They were about 126 miles SSW of Denver, near the famous Crestones. They rose 6000' above the broad, flat San Luis Valley to the west, with no intervening foothills. From the town of Crestone, Challenger was the high point of a towering mountain which appeared almost monolithic, and hid Kit Carson behind it.

Challenger and Kit Carson were barely inside the Baca Land Grant. Just to the north was the Rio Grande National Forest, and to the east, San Isabel National Forest.

The summit was smallish, about ten feet wide, falling off steeply to the southwest and northeast. The ridge dropped more slowly along its length, southeast and northwest. The top was covered with tundra and grass between flat, weathered boulders of conglomerate rock.

I heard about the naming proposal soon after it was made. I got in touch with the proposer and with the USGS, and wrote a letter to the BGN in support. When the name was officially accepted, I started to think seriously about commemorating it somehow. As far as I know, none of the Colorado Fourteeners, even those with commemorative names, has on the summit anything like a bronze memorial plaque.

I contacted the Colorado Mountain Club (CMC). They endorsed the proposal, but declined to arrange or join in any sort of ceremony. Dennis Williams was satisfied that the name was accepted, and also declined to climb the peak again. I contacted the Baca landowners by phone; they had little interest in or concerns about placing a plaque on the summit.

I posted a note to the USENET electronic bulletin board describing my desire to climb the mountain and install a plaque. This resulted in a number of people volunteering to join me in the effort or to make donations towards the costs. (The plaque cost about $180, and other items, excluding gas and mileage, phone calls, and photographs, added up to about $60 more.) We kept in touch by phone, paper mail, or electronic mail.

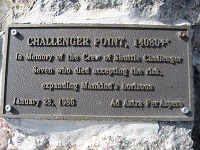

Jim Baer and I spent an hour on the phone one evening settling on the size and wording of the plaque. It was 6 inches high, 12 inches wide, weighed 6.5 pounds, and read as follows:

+---------------------------------------------+

| CHALLENGER POINT, 14080+' |

| |

| In Memory of the Crew of Shuttle Challenger |

| Seven who died accepting the risk, |

| expanding Mankind's horizons |

| |

| January 28, 1986 Ad Astra Per Aspera |

+---------------------------------------------+

The Latin phrase means: "To the stars through aspiration". It happens to be the state motto of Kansas. I ordered the plaque on May 23 from Craft Trophy of Fort Collins. Henry Fry was extremely helpful in getting it prepared quickly, correctly, and professionally.

[If I had to do over, I would change the wording a little. "In Memory of the Crew of the Orbiter" would have been briefer. And instead of "Mankind's" I would have said "Humanity's", even though a female member of our expedition said, "that's OK, I consider myself a member of mankind too."]

Around this time, Shepardson Elementary in Fort Collins, where I was a Visiting Scientist, held a balloon launch and fund-raiser for the project. They contributed $100. In the fall I made a presentation to them on the expedition, and helped construct a suitable display of clippings, photographs, and a rock from the summit.

The weekend of July 18th was a good target date for the climb because it fell in the middle of National Space Week. July 20 marked the 18th anniversary of the first lunar landing. It was late enough in the summer climbing season that the weather is (relatively) warm up there, and most winter snow was melted.

In May I mailed a press release to many people describing our plans. I also sent various entities, including Kennedy Space Center, pictures of the mountain taken from the air and from Crestone Peak.

In the weeks before the trip I busily overprepared. I made a long list of tools and supplies we might need on the summit, bought and tested a variety of concrete compounds, drew up a plan for how we might attach the plaque, gathered everything together and weighed the parts, and so forth. I'm still amazed at how much work (informal engineering, really) was involved in getting it right. Being uncertain of what to expect on the summit, I was prepared for a variety of alternatives. (But as it turned out, not quite everything!)

The weather did not look promising on Thursday night. But by Friday morning a "100% improvement" had occurred, according to Dave Randel, a CSU climatologist (and spouse of fellow Hewlett-Packard engineer Anny Randel). Instead of monsoon rains, we expected -- and received -- brisk, cold, dry winds from the desert southwest.

Friday afternoon (7/17) we took off from our respective workplaces. Jim Baer of Ball Aerospace came from Boulder with Barbara Roach, an accomplished mountaineer who climbed all the Colorado Fourteeners 10 years prior and had participated in many long expeditions to reach high summits. Ted Manahan of HP, Colorado Springs brought his wife Chuchang Manahan and eight-month-old son Clifton Manahan. We met late Friday night on the dirt road east out of the small, isolated town of Crestone, in the northern San Luis Valley.

On the way down to Crestone I stopped in Denver to show the plaque to the people at Channel 4 News. They ran a 45-second segment about our expedition on the Saturday evening news.

Saturday morning (7/18) we packed at the campsite. I distributed about 35 pounds of tools and supplies not normally carried to 14000', including the plaque itself. We drove about a mile further up to the trailhead, a total of 2.4 miles east of the center of town, on a rough and rocky road barely passable by passenger cars. We started on the trail at 0930.

Jim and Barbara took off ahead. I enjoyed a more leisurely pace with the Manahans and helped carry Clifton some of the way. We took 4:35 to travel the 2800' vertical, 4+ miles, on the sandy trail to Willow Lake, 11564'. The obvious trail climbed steeply to a gorgeous, oval, grassy meadow (Willow Creek Park), which was alive with wind-waves. Then it went a long ways up a narrowing valley, with many lazy switchbacks, to a hanging wall left by glaciers. Switching up this face past running creeks took one to the upper valley. The lake was about a half mile further along. The trail was up-and-down a bit at times, and somewhat swampy under the trees in spots.

Willow Lake was incredible. The downstream half was surrounded by big trees. At the upper end was a barren 200' cliff with a narrow vertical waterfall. We made camp right on the northwest lakeshore. Howling winds rushed up the valley all afternoon and most of the night, but the sky remained clear. Jim and Barbara ran up nearby Adams Peak, about another 2500' of vertical gain, while Ted and I circled the lake for a mellow hour and a half before dinner.

The nearby image is a view east (scanned from print) from Willow Lake to

Kit Carson Mountain (summit not quite visible), and nearer to the right,

Challenger Point (also summit not quite visible, but much of the steep

route is).

Beyond the lake you could see up the rest of the valley. Kit Carson loomed above the far end, and the broad, steep side of the Challenger ridge formed the right wall. There were willows and small pines scattered about. You couldn't see the summit of Challenger except from the top of the waterfall.

After dark, Joe Hunter, also of HP, Colorado Springs, arrived at camp wearing a headlamp. He pitched a tent and called it a night. We now had the traditional number -- seven, including the baby -- for a magic adventure expedition.

Sunday morning (7/19) Joe and I awoke at 0445 and left camp ahead of the others at 0530 as an advance party, carrying the essentials needed to begin placing the plaque. It was just light enough to make our way around the south side of the lake, a half hour before sunrise. The south side was rockier, but more direct than fighting through the willows on the other side. In 20 minutes we were above the waterfall. We turned right to scramble up the steepening mountainside.

We climbed a grassy and rocky slope up to the left side of a major

snow-filled gully. Here we met the first sunlight, which was much

appreciated, and proceeded up steep, knobby conglomerate. We reached

the ridge -- and the first sight of the splendorous view beyond to

Great Sand Dunes NP

and Blanca Peak group -- at 0755. A short ridge-walk to the left

brought us to the summit at 0805. Gaining 2500' in 2:35 wasn't bad,

with each of us carrying about ten extra pounds above and beyond the

usual.

We climbed a grassy and rocky slope up to the left side of a major

snow-filled gully. Here we met the first sunlight, which was much

appreciated, and proceeded up steep, knobby conglomerate. We reached

the ridge -- and the first sight of the splendorous view beyond to

Great Sand Dunes NP

and Blanca Peak group -- at 0755. A short ridge-walk to the left

brought us to the summit at 0805. Gaining 2500' in 2:35 wasn't bad,

with each of us carrying about ten extra pounds above and beyond the

usual.

For a short time we soaked up the panorama. Kit Carson dominated the skyline to the southeast, with Crestone Needle and Peak beyond it. To the right, the Sangre de Cristo Range curved around Great Sand Dunes NP to the Fourteeners near Blanca Peak. The open expanse of the San Luis Valley was bordered in the distance by the San Juans to the west. Mount Adams was a rugged pinnacle to the north.

We found and signed the summit register, which was placed in 1985. Dennis Williams was the last person to sign in during 1986, and only about 10 people had done so in 1987. The peak was seldom visited in the past, but will become more famous now that it's named. [By 2017 it was considered a separate Fourteener! And later, not again, because of insufficient saddle drop after precise laser measurements.]

People entered various positive comments in the log, like "Go at Throttle Up!" One person wrote a long diatribe about the foolishness of naming the mountain for Challenger; others added criticisms of that commentary. I mentioned that we were a plaque-mounting expedition, and a couple of choice quotes: "The Dream is Alive!" and "Earth is the cradle of mankind, but we cannot live in the cradle forever."

At 0815 we began site selection. There wasn't an obvious place to attach the plaque where it would be north-facing (out of direct, hot sunlight) and also more than a few inches above the ground. We rolled a few boulders out of the way looking for a good spot. We finally settled on the summit boulder itself, a hunk of very hard stone about four by six feet across, angled up from the ground to the southwest. Since the weather was good and we'd have time to drill holes in the rock, we were not so worried about thermal expansion.

In the course of moving some rocks piled on this boulder, I uncovered some "cremains", small chips of white bone, and a small, corroded brass token. On the front it said: "Ferncliff Crematory, Hartsdale, N.Y.", and on the back, a stamped number, "22510". This amazed me. Unfortunately I'd already disturbed the ashes, which were rather spread about anyway. We gathered most of the bone chips out of the way and continued working on the rock.

(After getting home, I called the crematory and discovered the ashes were of Russell Johnson Parker of New York, died September 9, 1949, at age 52. He was cremated on September 16 and the ashes were mailed to Walter H. Williams, no address recorded, on the 17th. We don't know when they were left on the summit, but apparently it was many years ago, judging by the condition of the crematory token. There is probably another long and fascinating story behind that.)

[Update 2017, a friend of a friend discovered the following through web research, which I paraphrased: Russell Johnson Parker was a mining engineer who traveled all over the world including the Congo. His passport states he was born 31 August 1897 in Olney Springs, Crowley County, Colorado. Had a nice picture of him. Handsome man about 5'11". In the 1910 census he was in Crestone, CO. His father appears to have died circa 1910 or so. By 1917 the family is in Denver, CO. He did study at the School of Mines in Colorado. His mother was listed as living in Denver, Sarah Parker (formerly Johnstone or Johnson). Was at 1081 Cherokee in Denver. His father was Daniel W. Parker. He had two brothers, George Washington Parker, born 13 June 1895, and Charles O. Parker, born September 1899.]

[Also: There were several Walter Williams in Colorado, and some that could have been friends of Russell Parker. Some in the Olney Springs area, and La Junta area as well. So, assuming that the Walter Williams mentioned was from Colorado and made the trek up to Challenger Peak.]

We decided to place the plaque on the flat, sloping upper part of the summit boulder. It was more horizontal than vertical, and faced northeast. First we chiselled a while to flatten the area, then started drilling anchor holes using star bits. This was very slow going, taking about 40 minutes per hole. (As an example of the kind of advance planning required, we had along and used a felt-tip marker to indicate where the plaque was to be set.)

The other three of the party left Chuchang and Clifton at camp at 0730 and joined us on top at about 1000. By then Joe and I had almost finished the first hole. We got two holes going at once, all of us taking turns pounding on the star bits (and occasionally, fingers). The temperature in the shade rose slowly from 30 to 40 degrees. The wind varied from dead calm to strong gusts. At one point some military jets came screaming across the San Luis Valley and around the peaks. A party of two climbers traversed about a hundred feet below, over to Kit Carson, without coming up to say hello. No one else visited.

At about 1215, four hours after Joe and I started site selection, we set the lead anchors in the holes. We discovered that, despite my overkill planning, we didn't have a proper anchor-setting tool. Fortunately, Joe had some construction experience. Not only did he do more than his share of the drilling (hammering), he also found a way to set the anchors using a screwdriver, and insured they were precisely positioned so the screws would match.

We prepared the rock by wire-brushing and otherwise cleaning it. Then after a bit of coordination, we briskly mounted the plaque. Two people mixed Quikrete, a fast-hardening concrete, while we squeezed silicone cement into the anchor holes, put modelling clay plugs on top, then coated the rock with acrylic bonding compound. We put several of the bone chips on the prepared rock. Then we spread the concrete, positioned the plaque, and tightened it down, forcing cement out around the edges. We used three stainless steel and one (longer) steel Allen-head cap screws. They look good, and are very strong and hard to remove.

The rock was cold. The Quikrete set more slowly than when I experimented with it at home. However within half an hour we could gently smooth the edges to the rock. Meanwhile, someone plastered a nearby rock with extra cement and set the crematory token into it.

We forgot to cover the plaque with duct tape and plastic, so we had to clean it up a little with a toothbrush and rags. We took zillions of pictures, and the rest of the party headed down at 1345.

I didn't want to leave. It was so incredible, finally being there and done with the project. I slowly gathered myself after the frantic pace, picked up odds and ends and stuffed them in my pack, coated the concrete with silicone cement to help protect it, and took more pictures.

Now this was a magic time... It was quiet, peaceful, and there was the culmination of our hard work, gleaming in the sunlight. I was tired, and a little overwhelmed with many feelings. I wanted to capture the moment. It's always hard to do.

The view to the southwest was phenomenal. The summit boulder, the plaque, a rock cairn, a wooden pole, and behind, Crestone Needle, Crestone Peak, the Great Sand Dunes, and in the distance, the Blanca Peak group. From here, the horizons were indeed very far away.

One nearby image (click to enlarge) is of a framed photo that's hung on

my wall for years with a tracing of the plaque (before it went up on the

mountain) attached below it.

One nearby image (click to enlarge) is of a framed photo that's hung on

my wall for years with a tracing of the plaque (before it went up on the

mountain) attached below it.

I hope the plaque lasts for a long time. Long after people who come to the summit, who remember the Challenger and her crew, have forgotten how it came to be there.

"The greatest use of life is to spend it on something that outlasts it."

-- James

[Over 35 years later, the plaque was still on the mountaintop!

Amazing.]

After our work was done, I took (and later scanned) a photo of the other

four climbers, left to right: Ted Manahan, Joe Hunter, Barbara Roach,

Jim Baer.

After our work was done, I took (and later scanned) a photo of the other

four climbers, left to right: Ted Manahan, Joe Hunter, Barbara Roach,

Jim Baer.

Finally, I covered the plaque with a sheet of black plastic weighted down with rocks, to help the concrete dry slowly. I shouldered my pack (too heavy!), and started down at 1455, after 6:50 on the summit. In 15 minutes I reached the 13800' saddle northwest on the ridge above the gully. I carefully descended along the gully, and then glissaded down it and a number of lower snowfields, reaching the flats above the lake at 1555. By 1615 I was back at camp.

Joe had already departed. The others were half packed. They left at 1640. I finally followed them at 1730, and never did catch up to them during the slog out. At 1930 I reached the trailhead and my car, the last one remaining from the weekend.

I took it slow going home. Down in Crestone I watched the last sun strike Challenger Point almost an hour later. I camped for the night very late, on the Weston Pass road southwest of Fairplay, and reached Fort Collins at noon on Monday (7/20). Soon after, I was interviewed on the phone by the Rocky Mountain News, which ran a followup story on July 21 (page 25) to their earlier story on July 17 (page 26).

The next day I was still unusually sore and tired from the hard workout. That faded, but the memories will not.

Some months later I mailed a copy of this report and some pictures to Dr. June Scobee, wife of the shuttle pilot, care of the Challenger Center she created. Eventually I received a very nice reply, including a thank you note written on a copy of the map quadrangle showing the peak. So she, and perhaps the other astronauts's families, are aware of Challenger Point and the memorial plaque.

Years later I received a spectacular photo of the plaque taken by

Leith Johnson

on August 26, 2001.

.

.

.

.

And years after that, I received from astronaut

Mike Mullane

of New Mexico some photos taken in 2008 and 2020, showing how the plaque

is (slowly) degrading over the long run:

And, check out this essay Mike wrote after interviewing me.

(end)

(Next trip report: 1987_0802_Paiute,Audubon.htm)